WRITINGS ↓

My writings explore the rift between nature and culture, the opposition between humans and the environment, and thus between buildings and landscapes.

Excerpt number one ↓

In the Ruins of the Anthropocene.

Piercefield, Soane, and the birth of naturalism

“In this age of research when the Connoisseur and the Antiquary find a lively interest in whatever relates to former times & their attention is thereby frequently directed to the investigation of things which, at least to common minds, seem of little importance, no wonder, in such an age, so much notice has been taken of the ruins and very extensive assemblage of fragments of ancient works.”

With these words, in the poem “Crude Hints Towards an History of my House,” the architect John Soane imagines an archaeologist examining an assemblage of fragments to speculate on the origin of Soane’s unrecognised and unrecognisable work. In the poem, with the skills of a storyteller, the celebrated eighteenth-century architect envisions an age of research in a far away time, where a scholar spends his days in an attempt to understand the past through the study of ruins. Although this poem refers to Soane’s own house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, what is today an orderly museum, this chapter will examine the actual ruinous remains of one of Soane’s lesser-know works, along with the landscape park that surrounds it, arguing that these ruins present some of the first traces of the tangible environmental changes that have affected the Wye Valley. The eighteenth-century development of Piercefield Park will thus help us to trace the early effects of the romantic influence on the Wye landscape. Meandering through its walks allows us to recognize that the Picturesque landscape is not only a manifestation of the human ability to transform topography into a two-dimensional representation, but also a meaningful response to environmental changes, signalling the entrance of the Anthropocene. Given how these design forms originated in light of the environmental changes wrought by early industrialization, they allow us to tie the development of Western naturalism as an ideal to the advent of the Anthropocene. In recounting this evolution, furthermore, we can relate these developments to the moment when landscape began to separate from architecture and gain intellectual autonomy of its own, offering a historical, and ultimately ecological, perspective on the categories that have come to shape contemporary practice.

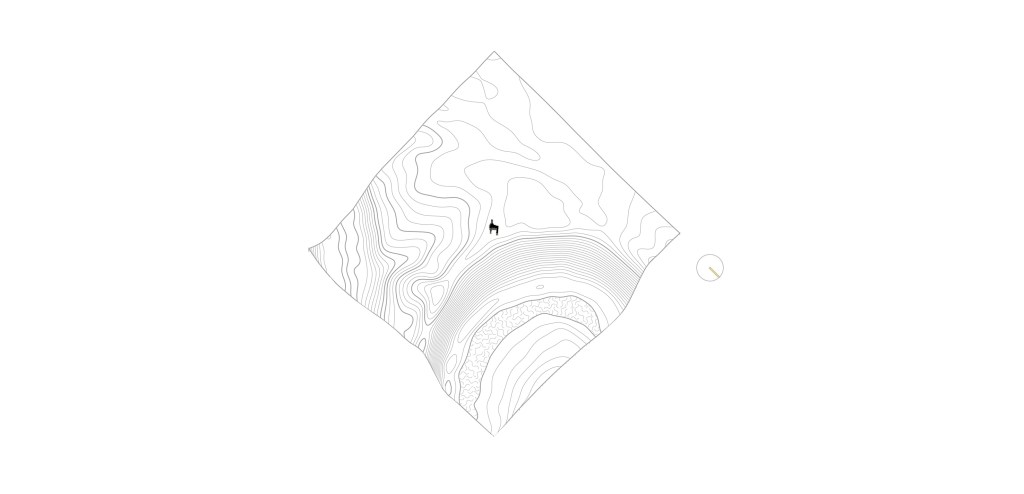

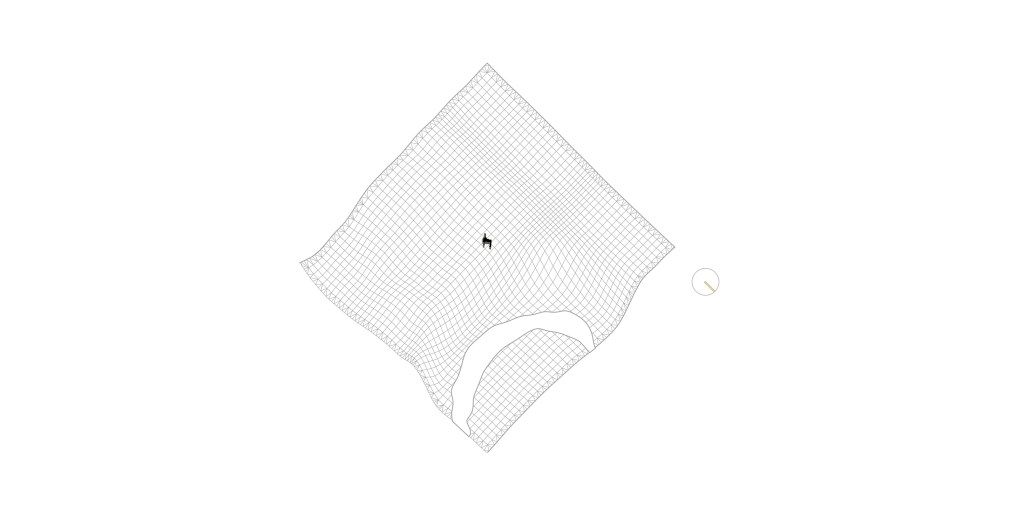

Topography

Located on the western bank of the River Wye, three miles south of Tintern Abbey, Piercefield Park was an important stop along the river journey that took tourists by boat from Ross-on-Wye to Chepstow. The abbey is not just a geographical reference point, but also one of the reasons why the park emerged along this route. The ruins of the 12th century Cistercian Abbey had already become know as a “romantic” destination by the 1750s, attracting poets, intellectuals, and artists from throughout the country.[1] These romantics’ renewed appreciation for nature can be attributed to their encounter with an agricultural landscape already punctuated by the earliest forms of industrialization. And, inspired by Picturesque ideals, the birth of the staged wild park was quick to ensue. It is important to underline how the topography played a crucial role in these developments. The need for water and reliance on hydropower required the early industrial sites to be situated along the upper reaches of the stream, in the open countryside and not in the villages.[2] The Whitebrook Valley, a few miles north from Piercefield, shows just such an evolutionary path. Considering how it appears today, it is hard to believe that this remote place with its steep, well-wooded valley sides and scenic houses was once a hive of industry: the brook provided a flow of water used as a source of power with no fewer than fifteen dams active at any given point.[3] With large-scale paper production beginning around 1760, the village developed around the mill, with most houses built for the workers themselves.[4]

Romantics arriving to the area recorded the juxtaposition of these two worlds, the Picturesque and the industrial. In a poem dated July 13, 1798, Wordsworth describes his view of the valley as ‘’green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke / sent up, in silence, from among the trees.’’[5] In the poem, his understanding of the landscape is strictly connected to his sensorial vision of a working landscape. As Dewey Hall elucidates, it is evident that Wordsworth’s journey would have presented him with pastoral scenes interspersed with the markers of industry.[6] Thus William Gilpin, the father of the Picturesque, once described the artifice behind Piercefield, recounting how “the winding of the precipice is the magical secret, by which all these enchanting scenes are produced,”[7] where the “magical secret” refers to the existing topography with both its natural and artificial features. And yet, across the landscape extensive charcoal manufacturing would have produced smoke about whose source Wordsworth could hardly have been uncertain. It is clear, therefore, that both the Picturesque park and the industrial landscape flourished in this specific place because of the role that topography played. What it is less clear are the circumstances that allowed one to overtake the other, with the industrial legacy disappearing incredibly fast and the park still visible today.

Environmental responses

The Piercefield walks, as they appear today, are light human traces crisscrossing two miles of land left by the tourists who have stridden these grounds for the past two centuries. The house stands atop a cliff, at the point where the river Wye snakes around the valley to form an S-shaped turn. Although the site shows archaeological signs of settlements dating back to the 14th century,[8] it was not until 1736 that the land was remodelled as a Picturesque idyll to embody the spirit of its time. After several ownerships, Valentine Morris focused on developing the landscape.[9] When in 1784 Morris, debt stricken and unable to make any profit out of the estate, was forced to sell the property to George Smith, the latter added a remodelled architecture to the already celebrated set of walks. It was at this turn that the Wye encountered one of the most celebrated architects of the 18th century.

In 1785, just one year after the property has been purchased, a rather inexperienced John Soane, having just being introduced to Smith by one of his grand-tour friends, [10] set off from London to visit the estate. Three years before his celebrated appointment to the Bank of England, his career was not taking off as he had wished, and he spent most of his time working on country houses. The relationship between Smith and Soane proceeded slowly and was marred by both financial and collaborative difficulties. After several years of disputing, however, the plans were largely settled by 1792, with only minor changes indicated in drawings from the following year.[11] Yet the final outcome, notwithstanding the dozens of drawings issued in this seven year process, is just a façade—almost an identical copy of Shotesham Hall, a house that Soane had recently completed in Norfolk.[12] Most probably the reduced scope of work was the result of the client’s financial constraints. What is certain is that on the 10th of December 1793, London’s auction house Christie’s listed the house for sale with its roof still to be completed.

Although it would be difficult to assess Piercefield as an individual piece of work, its design contains several identifiable themes that ultimately expose the thinking behind Soane’s interventions and suggest that Piercefield can be understood as part of a sequence of country houses. Although here he was working around an existing building, the “symmetrical axis” typical of Soane’s other country houses is still visible in the elevation. When looking at the building as a silhouette in the landscape, some of its elements are exaggerated, and in the resulting visual composition the wall recesses and chimneystacks become a focal point, almost a Picturesque response to a classical facade. As Dean Ptolemy points out, Soane’s use of Ashlar for the façade gives the structure a uniform look that is identifiable as “primitivist” and in line with his interest in the mythological “primitive hut” that signals the origin of architecture. Alternatively, this could be interpreted as an attempt to instil a sense of purity and simplicity in response to the unstoppable advance of the “technology, mechanization, decadence and wealth” of his time.[13]

The restrained design of the façade and the series of rolling walks seem to be the expressions of two different architecture languages, as if the philosophies that shaped the park and the house in contradiction with one another. Indeed, the late 18th century scene bears the mark of both the rationalist ideals of the Enlightenment and the values of Picturesque romanticism. Through these seemingly incongruous forms, Piercefield’s eighteen-century English garden was the site of a confrontation between the experiences of rationalized, classic architecture and “wild,” sentimentalized nature. The apparent tension between Piercefield’s two competing styles bespeaks the emergent separation of landscape and architecture within the English context. As Clemens Steenbergen and Wouter Reh note,

The most important change in the English landscape garden over against the villa and the French garden was the breaking up of the unity of the architectonic composition, so that the references back and forth between architecture and landscape were no longer complete within one formal model, but were brought to the level of individual experience.[14]

Although this divergence has been attributed to the professionalization of architecture and the increased complexities attributed both to technology and planning,[15] the example of Piercefield demonstrates that the separation of architecture and landscape was also grounded in a conflict between the influences and references of two very different idioms.[16]

The inconsistency of Piercefield’s two styles is crucial for understanding Soane’s architectural and intellectual vision. Described by architectural theorists as “the erudite and eccentric synthesizer of various and sundry currents of eighteenth-century British and Continental thought,” Soane’s ability to represent different worldviews is indeed central to the role he had in architecture theory. [17] Although for a long time his practice has been interpreted as part of the classical tradition, contemporary scholarship has been more careful to explore his connections to the Picturesque. Jonathan Hill’s account of Soane’s connection to the Picturesque, for example, mentions both the architect’s private collection of books with titles such as Observations on Modern Gardening and his travels to gardens like Studley Royal in Yorkshire in 1816-1817. Yet Hill never mentions Piercefield in his narrative, which focuses on a period of Soane’s career some twenty years after his work in the Wye. It is clear, however, that Piercefield already bears an important connection to the Picturesque, and that Soane intended this work at least in part as a response to the environmental changes happening around him.

Geology of the contemporary

Soane acquired Observations on Modern Gardening in 1778, seven years after he first visited the Wye. Written by Thomas Whately the year before, the book does more than demonstrate Soane’s awareness of the relevance and national importance of Piercefield as a Picturesque landscape park. For Whately also introduces one more theme, that of the importance of ruins:

This lawn is encompassed with wood; and through the wood are walks, which open beyond it upon those romantic fences which surround the park, and which are the glory of Persfield….The woods concur with the rocks to render the scenes of Persfield romantic; the place every where abounds with them; they cover the tops of the hills; they hang on the steeps; or they fill the depths of the values….In many places the principal feature is a continued rock, in length a quarter of a mile, perpendicular, high, and placed upon a height: to resemble ruins is common to rocks; but no ruin of any single structure was ever equal to this enormous pile; it seems to be the remains of a city; and other smaller heaps scattered about it appear to be fainter traces of the former extent, and strengthen the Similitude.[18]

From Elisabeth Whittle’s archaeological analysis of Piercefield, we know that there would have been hundreds of sculptural fragments gathered around eight points around the property.[19] This would have been a collection of individual pieces not dissimilar to those Soane gathered in his own house museum or commissioned for his collection of architectural paintings. Both in Soane’s work and in the park at Piercefield these “stones,” although ichnographically borrowed from a classical tradition, become more than a simple manifestation of time. They become a symbol of the force of geological transformation. The potent symbolism that the imagery of ruination had for Soane and his contemporaries is evident in Joseph Gandy’s painting of Soane’s Bank of England, which envisions nature’s ultimate triumph over the ruins of the latter. Here, we encounter architecture transforming into landscape, and are thus reminded of man’s apparent insignificance when faced with the ineluctable progress of geological time.

The imagining, staging, and exploitation of ruins remains of great significance in the age of the Anthropocene, where they have continue to remind us with our place within the overwhelming scale of geological time.[20] Indeed, the cyclic rhythm of imagery found in the paintings commissioned by Soane is not far from that found in the images of derelict post-capitalist cities that we are used to seeing in contemporary “ruin photography.” Yet the two styles bear an important difference, for they refer to entirely different agents of transformation and decay. Although she encounters a similar image, the observer in the Anthropocene knows that the ruins are not just a product of a heteronomous natural force, but of the observer and her fellows themselves. We have become the very geological agent responsible for the drastic transformations of reality.

What is obvious from our scientific perspective today was, nonetheless, already becoming apparent in the decades after Soane’s work at Piercefield. By the 19th century, that is, many had come to recognize our undeniable presence on earth as a geological force—that human civilization is not a mere innocent and helpless victim of the “natural” transformations that it confronts, but their very author. Consider, for example, architect and social critic John Ruskin’s 1851 account of how new geological discoveries had thrown earlier worlds of human meaning into doubt—especially those of religious experience:

You speak of the Flimsiness of your own faith. Mine, which was never strong, is being beaten into mere gold leaf, and flutters in weak rags from the letter of its old forms.…If only the Geologists would let me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.[21]

For a generation conscious of the Anthropocene,[22] these words speak a familiar language. Indeed, we are more conscious than ever before of just how significant our impact is upon the ecological systems of which we are a part. And, just as we face the urgent need to ameliorate this impact today, so too did the rise of naturalist ideals in the 18th and 19th make many aware of the need to “preserve” the English landscape from the threats posed by industrialization. These efforts would ultimately lead to a powerful conservationist movement, culminating in the early 20th century in a set of wide-ranging planning efforts that form the topic of our next chapter.

***

Piercefield house today appears to the wanderer as a lifeless façade, almost a stage set, showing the signs of the abandonment that since its closure in 1850 have transformed it into one of the timeless ruins appearing in Gandy’s paintings. Given its architect’s artistic vision, this is surely a fitting stroke of historical fate. Emphasizing the origin of the park as a result of an adaptation to the morphological characteristic of the Wye and reflecting on the cultural and temporal aspect of nature, we’ve seen how Piercefield was the product of an aesthetic vision for a landscape where Enlightenment rationalism is directly confronted with the wild, untamed forces of a romanticized nature. This is an aesthetic that brilliantly mirrors the broader intellectual context of the period, which saw a burgeoning naturalist philosophy confront the forces of scientific industrialization early industrialising is the starting point of a trajectory parallel to the birth of naturalism in western society. As such, Piercefield allows us to understand the establishment of landscape’s autonomy domain vis-à-vis architecture as the result of attempts to protect and preserve an objectified nature from the illegitimate incursions of the foreign invasions of culture.

[1] Whittle, Elisabeth. “‘All These Inchanting Scenes’: Piercefield in the Wye Valley.” Garden History 24.1 (1996): 148-161.

[2] Steenbergen, Clemens and Wouter Reh. Architecture and Landscape. The Design Experiment of the Great European Gardens and Landscapes. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2003, p. 230.

[3] Tucker, D. G. “The paper mills of Whitebrook, Monmouthshire.” Archaeologia Cambrensis 121 (1972): 80-96.

[4] By the late 1880’s the industrial presence in this area ceased. Today, very little remains of what once were a thriving industry. The buildings of Fernside Mill remain externally intact, as the last symbol of a laborious past.

[5] Extract from the poem “Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey”.

[6] Hall, Dewey W. Romantic Naturalists, Early Environmentalists: An Ecocritical Study, 1789-1912. Farnham: Ashgate , 2014, p. 126.

[7] Fosbroke, Thomas Dudley and William Gilpin. The Wye Tour, or Gilpin on the Wye. Ross on Wye: W. Farror, 1834, p. 105.

[8] Murphy, K. “The Piercefield Walks and Associated Picturesque Landscape Features: An Archaeological Survey.” Cambria Archeology – Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited , 2005.

[9] Whittle, Elisabeth. “Piercefield Park and the Wyndcliff .” Site Dossier. CADW, 1991.

[10] As shown in the project’s description held at Soane’s library, the architect was introduced to Smith by Rowland Burdon. After returning to London from his travels, the young architect had hoped that his European grand tour would have given him the opportunity to meet the clients for great commissions.

[11] These information are taken from Soane’s Account Journal consulted in Soane’s library.

[12] Darley, Gillian. John Soane: An Accidental Romantic. London: Yale University Press, 1999, p. 63.

[13] Dean, Ptolemy. Sir John Soane and the country estate . Abingdon: Routledge, 2018

[14] Steenbergen, Clemens and Wouter Reh. Architecture and Landscape. The Design Experiment of the Great European Gardens and Landscapes. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2003, p. 387.

[15] Shepheard, Sir Peter. “Introduction to Modern Gardens (1953).” Birksted, Jan. Relating architecture to landscape / edited by Jan Birksted. London: E & FN Spon, 1999. Pp.17-21.

[16] Cf. Odenthal, Luke. “Visions of Nature in the Eighteenth-Century English Landscape Garden.” MURAJ 1.1 (2018).

[17] Mallgrave, Harry Francis. Modern architectural theory a historical survey, 1673-1968. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, p.63.

[18] Whately, Thomas. Observations on Modern Gardening. London: T. Payne, 1770.

[19] Whittle, Elisabeth. “Piercefield Park and the Wyndcliff .” Site Dossier. CADW, 1991.

[20] Zylinska, Joanna. Nonhuman Photography. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017, p.9.

[21] Townsend, Francis G. Ruskin and the landscape feeling : a critical analysis of his thought during the crucial years of his life, 1843-56. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1951, p. 61.

[22] Macfarlane, Robert. “Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet for ever .” The Guardian (2016).